Willis Morris is a rock climber, winter climber, alpinist, speedwing pilot and member of the Jöttnar Pro Team. At only 20 he was part of the youngest-ever team to climb what was then the hardest route on the Eiger’s north face. As a self-taught speedwing pilot and increasingly accomplished alpinist, the combining of these two disciplines into a new form of high octane ‘para-alpinism’ was inevitable.

We caught up with Willis at his Glasgow home.

You began climbing at the age of 10. Tell us about that, and your journey over those first few years.

Willis: The same as many climbers nowadays, my first time climbing was at an indoor wall. My parents weren’t climbers, however were keen outdoor enthusiasts and hillwalkers. One rainy weekend ruined plans to head up a munro and instead ended with a taster session at the local rock gym and finished with me completely hooked on climbing. Several years of indoor training, youth competitions and general obsession with the sport lead me to building strong partnerships with other young climbers who together we slowly built the experience and skills required to push our climbing into the outdoor disciplines.

Looking back, there was definitely a feeling of ‘ignorance is bliss’ in the early stages of near misses and ballsy risk taking. Having a young, gung-ho attitude fuelled the motivation for the group but it also created an environment where there was a real drive to push yourself and learn where the limit of your risk acceptance was. I think starting out like this was risky, however that exposure to risk fast-tracked our learning exponentially and our reckless approach was quickly outweighed by the large bank of skill and experience that we accumulated. We were left as a group of strong youths that were keen and willing to push hard outdoors, yet had a background of knowledge that vastly exceeded that of much more experienced climbers.

By 15, you’d moved into winter climbing. Describe the mental and physical transition involved.

It’s a funny one really, winter climbing seemed like such a niche, that especially as a teenager, was almost impossible to get involved in. Finding a partner who was as keen to take that first step, with little information on what was involved or how to go about it all was the key.

Regardless of your climbing ability, winter climbing when you are young is hard going. Getting to the mountains is difficult if you don't drive, access is limited to crags that are within distance of public transport and hitchhiking is a pain. Once you finally manage to reach the crag, the walk-ins feel brutal. Compared to a day out trad climbing, a day out in winter felt really tough, both physically and mentally. All the additional kit loading you down, the logistics of weather forecasts and conditions being an added obstacle to a day's climbing. I definitely felt like it was a large step in maturing as a climber to decide to go out in winter. Everything about it felt more serious than just a fun day out, playing on a summer crag. I can see why it's hard to start as a youth and why so many beginner winter climbers give it up before they ever truly get into it. For me, that added struggle just added to the excitement of the challenge.

I always remember having older climbers pass us by at pace on the walk-ins. They made it look easy in their Gucci lightweight boots, with the latest tech axes strapped to tiny packs. These guys were seasoned wads. We on the other hand were slogging up in hired B3s, heavy steel shaft axes that we’d borrowed off one of the old blokes in the centre, two 60m, 10mm single ropes, which we planned to use as halves, and bags that weighed the same as us! It was incredible to see how effortless people made it all look. How fit they were, how efficient their movement was and how steep the routes were that they were climbing. That was the real inspiration for me, the dream that kept me slogging away, determined to learn and improve. I wanted to move on from the grade 2 gullies and onto the steep mixed lines, I wanted to be a ‘proper’ winter climber, it was just so damn cool!

Will someone who’s good on rock naturally also be a good winter climber?

I’m not sure there's a perfect recipe for a good winter climber. Sure, having a background on rock will help you along the way and knowing how to place gear well will certainly help as gear in winter can be hard fought at the best of times, and you need to know that what you do manage to place is going to hold. However, winter is such a different beast that especially whilst learning, it tests a climber in more ways than just their ability to move well. I think someone that knows how to dig deep when they're exhausted, and stay motivated and determined regardless of how brutal the weather is will fare much better on a winter day than someone who can pull hard on small holds. Having the grit to battle the cold and conditions, the endurance to last for a 16-hour day and the mental fortitude to keep your cool when you have to pull on that scary hook, far above the last runner is what really separates those that will excel in Scottish winter. You need to really want it.

So in pursuit of more suffering, you turned your sights on the Alps, ticking some of the classic north faces.

Tell us more about that.

It was a logical step really. Scotland is magnificent, but the magic of climbing in the Alps was just something else. It was really just a quest to climb something bigger, to see what I was capable of and experience being on those mountain faces that I'd only ever read about in books. When Robbie Phillips invited me to join him on an alpine trip to tick off some of the hardest routes around, I jumped at the chance. I knew it was unlikely we’d achieve what we set out to climb, I knew some of the climbing was beyond me, that I wouldn't be able to climb every pitch, but I also wanted to test myself. I wanted to see what it was like to be completely out of your comfort zone and see how far sheer determination could take me. I learnt so much in that summer, not only about my climbing and where I wanted to go with it in the future, but also about how far I was able to push myself. We ticked off several big routes, including being the youngest team to complete ‘Paciencia’ - what was at the time the hardest route on the north face of the Eiger.

And then came speedflying. What is that, and what was your journey there?

Returning from that same summer alpine trip, I’d been inspired to take up flying after witnessing a pair take off from the summit of Brevent after climbing a route next to us.

I’d never been that inspired by paragliding in the past, the equipment was large and cumbersome, the weather needed to be just right and as much as flying down from a hill looked more appealing than walking, it just didn't look exciting enough for me. Then I saw speedflying. Tiny wings, sub 2kg packs, launch them almost anywhere, unbelievably fast, (120km/h!) and able to stick with the terrain and proximity fly back down the face you’d just climbed. Yeah, that was more up my street!

I put climbing aside for a full year to dedicate myself to the dream of learning to fly. Countless days of kiting wings, analysing weather forecasts and slowly building up airtime under a wing. Being careful but also fully committed, I was obsessed with improving. Hundreds of flights went by in less than a year. I was on a mission. I didn't realise the level I was at until I started to fly with others. Experienced pilots, who had doubted my rogue entry into the sport were now in disbelief at the progress I’d managed to make in such a short time. Suddenly I was the one answering questions, not asking them. Pilots wanted advice and feedback on their flying from me, and suddenly I was the one pioneering, flying impossibly small wings at a level not seen in the UK before. Dedicating your time and focus entirely to something pays off. When you really want something, regardless of the odds, it's almost always achievable with enough sheer stubborn determination!

Climbing up and then flying back down seems the perfect combination. In what ways do the two disciplines complement each other?

I hate walking downhill. It's tiring, the riskiest part of the day and trashes your knees and feet. Unfortunately, I love spending time in the mountains and coming back down is an unavoidable part of being up high. So being able to combine an aerial descent, with lightweight equipment that easily fits in a climbing day pack was ground-breaking for me. Routes that were long, with descents that took hours or required you to be back in time to catch the last lift back to the valley were no longer as stressful or time pressured. With a good forecast and a launch site scoped out, the mountains became a playground, not just for climbing lines upwards, but combining that with dream descents. It's an odd feeling to start getting excited about the line you’ll take for descent after years of dreading that part of the day.

Choosing a way down that can be flown hard and close to the ground to make it as gnarly and thrilling as the ascent became a crucial part of building a plan for a day in the mountains. There’s certainly a bright future for this combined style - this ‘para-alpinism’ with endless possibilities.

You featured in Jöttnar’s short film, Facing Goliath, shot in the Skye Cuillin. What’s the experience of filming like?

It can be really cool to work alongside such amazingly talented people, who clearly have so much passion for their jobs and the work that they produce. I also love to geek out on some of the camera kit too, especially drones!

However, it’s definitely not all gadgets and posing in front of beautiful scenery. A day's filming is so different from a day out on the hill for fun, but not necessarily in a bad way. You can imagine the process of filming in the mountains is a difficult one. The logistics of cameras, angles, light, safety, ropework and communication are all extremely difficult to get right, especially in an extreme environment. For every five second shot that you see in the finished film, there might have been hours of preparation for that single moment or multiple takes of the same action shot, just to capture it perfectly. I quite enjoy the process to be honest, seeing a lot of prep work all come together, improving the shot every time you repeat the action so that as a team, both in front and behind the camera, you’re slowly getting closer to the director's vision that they are trying to create. When you manage to get it just perfect, it can be really satisfying.

And on the subject of filming, you’ve been doing some stunt doubling and behind-the-scenes movie work of late. Can you talk about that?

Not just yet! It involves speedflying in some really remote areas of Scotland and opening some outrageously cool descent lines on mountains that no one has ever flown from before. There will be a lot of good footage to release soon so watch this space...

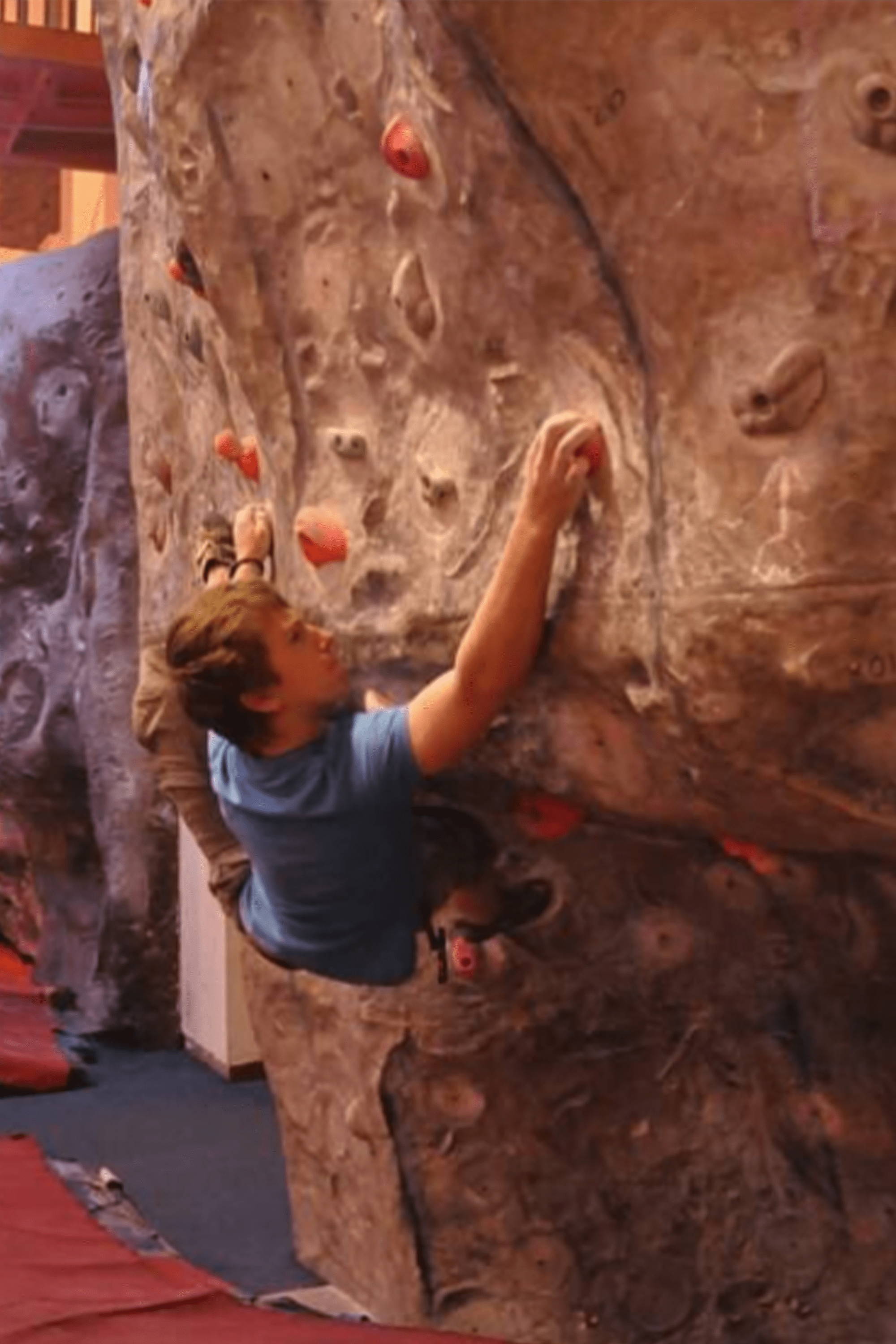

The idea of starting the club was born during the Covid lockdown. With winter in full swing yet the mountains off-limits, cabin fever led us to construct a purpose-built dry-tooling home wall in our Glasgow-based garden. As members of the GB Ice Climbing team, we focused our energy on preparing and training for the Ice Climbing International competitions. As our abilities (and the home wall) grew, so did our enthusiasm for sharing our passion with others and once the world opened again, we just had to start a club to be able to manage the demand from people wanting to get involved.

For the uninitiated, dry-tooling involves climbing with the use of ice axes and crampons/fruit-boots on dry rock in specified venues which are unsuitable for other types of climbing. It's exceptionally good strength training for winter routes. An indoor equivalent also exists where climbers will use not only regular indoor climbing holds but also technical metal holds, wooden kickboards, and of course real ice in the form of hanging barrels. It's sport climbing on steroids! As the UK’s only club of its kind, we wanted to introduce the sport of dry-tooling and competitive ice climbing to new climbers and offer a safe and supportive training opportunity for experienced toolers within Scotland. We aim to remove the old reputation of the sport and make it a common goal for climbers to want to progress in tooling, the same as they would in other disciplines. Dry-tooling may be the ‘dark art’ of climbing - but it can also be incredibly fun - and we aim to give club members, complete novices and masters of the sport alike, as many opportunities to participate in the wonderfully chaotic world of climbing with axes.

Two years on from starting the club and we are now pioneering the way for competitive ice climbing across the globe. We’ve run dozens of events across the county, have hundreds of members signed up, we’ve run multiple international competitions here in the UK and have introduced and trained up many athletes who have won multiple world championship titles and podium positions in all age categories and disciplines.

You put an ice pick through your hand not so long ago. What happened, and how’s the recovery?

Playing with sharp, pointy things is never without risk! I had an unfortunate accident whilst training for competitive speed ice climbing, Yeah, that's a thing! Just like in the Olympic discipline for rock, it's all about climbing a wall fast, but it's on real ice, with ultra- sharp axes, so there's little room for error. Consequences can be substantial puncture wounds, as I unfortunately found out the hard way. I broke a few bones, severed a tendon and almost tore a finger clean off. I’ve still got a way to go before I’m fully recovered and able to rock climb at my previous level. However, just four months post-surgery, I'm back wielding axes again. I managed to compete in the ice climbing World Cups in Europe recently and I'm back in the mountains making the most of the winter conditions, so I'm keeping optimistic that I will make that full recovery.

And to the future – what do you have your sights on?

Returning back to my full level of climbing after this recent injury is my top priority just now. Looking further forward I'm keen to knuckle down and focus on one or two disciplines to really push my grade in them. I’ve always been a keen all-rounder, and keeping fitness and ability at a high level across the board is a tricky thing to juggle. The last few years I've felt I have really consolidated a solid base across the board so I’m feeling it would be a great time to try and push that base into a pyramid with a focus on one or two disciplines.

A big trip to the Greater Ranges is also on the cards for 2024, and is something I've always wanted to do. The large mountains are somewhere I feel there is a lot of potential to combine my skills as an all-rounder both on the ground and in the air into a pretty awesome project.

Willis Morris is a member of the Jöttnar Pro Team. Read more about him here.