Following the travel restrictions of the last two years, I was yearning for an adventure to a completely new place and searching for fresh experiences. As a mountain guide and skier, I feel fortunate to be able to align my passion with my work; yet a simmering frustration lingered from the difficulties of the past two years.

When Slovenian skier Bine Žalohar reached out to me with a trip proposal and showed me a picture of the remote north face of Falak Sar (5,962m), the highest peak in Swat, Pakistan, it instantly piqued my interest. A stunning ski line on an un-skied mountain at a relatively amenable altitude, meaning we wouldn’t have to spend weeks acclimatising. As far as ski mountaineering goes, this entire region of the Hindu Kush range looked to be untouched.

The Swat Valley of northern Pakistan, in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, is certainly not an internationally renowned tourist destination as we found out, yet this is where our team of five traveled to in May. Our Chamonix-based cohort consisted of Bine, an ex-professional freestyle skier turned ski mountaineer, Aaron Rolph, a British photographer and skier with a real appetite for adventure, Juliette Willmann, a young French freeride star, and Beth Healey, a British expat doctor with multiple arctic expeditions under her belt.

While not famous for its skiing, the Swat Valley did gain international notoriety following the takeover of the Pakistani Taliban in 2007. This is where Pakistan’s Nobel Peace Prize laureate Malala Yousafzai was shot in the head in 2012, when as a schoolgirl she defied the Taliban. Although the security situation in Swat is now stable, there have been virtually no foreign tourists of any kind to the region for years.

Upon arriving in Islamabad, we immediately got a warm greeting from our agency, and before long we were heading towards the mountains in our minibus past a sign declaring Swat to be the ‘Switzerland of Pakistan’. After entering the Swat Valley, an armed police escort suddenly appeared in front of us, which continued in slick relay fashion from village to village until we eventually reached the end of the road and our staging point, Kalam. From Kalam we got the first views of countless unclimbed and un-skied high alpine peaks, providing a glimpse into a bygone era of untapped mountain ranges.

Beyond Kalam, we drove for six hours by jeep up the lush and beautiful Ushu Valley, past remote villages and beyond the reaches of any paved road. Our core team of Pakistanis, Ahmad our guide from Kalam who had been involved in a successful 2020 Pakistani expedition to Falak Sar, and Zaheer and Nazir, our cooks, were joined by 26 porters (a surprisingly large number) to carry all we needed to basecamp. At the final village, I was asked to stop by the local police station and then told by the policeman there I had to sign a document waiving responsibility of the authorities for our safety. I hoped this was simply a formality.

It took two days of hiking for our team of now 30-plus to reach the spot we designated for our basecamp at around 4,200m. The route was more arduous than it should have been for the five of us all came down with sick stomachs and some violent diarrhea, frequently stopping behind boulders while it was raining and snowing.

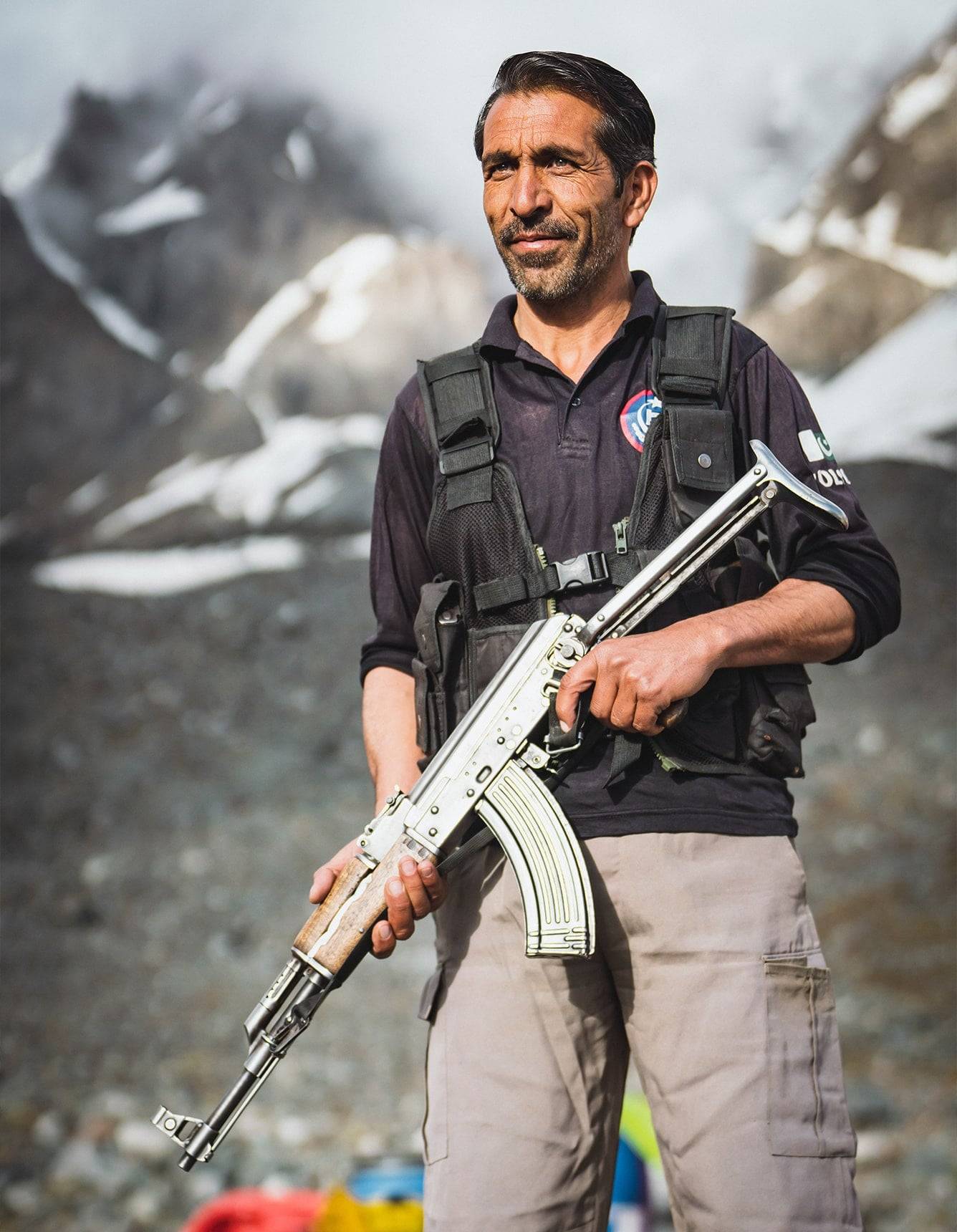

At basecamp we were soon joined by Sattar, an amiable local police officer and veteran of fighting the Taliban, who took it upon himself to hike up carrying barely anything save his trusty Kalashnikov rifle, which we noticed was an extension of his own being. Our team at basecamp now consisted of nine of us, and we were exceptionally well looked after by the Pakistanis, who were from diverse backgrounds themselves.

Sattar and Ahmad were ethnic Pashtuns and Wahhabi Sunnis, making them, on paper, aligned with the least tolerant form of Islam, yet they were open minded and accepting of all of us, Beth and Juliette included. Nazir and Zaheer were Shia Baltis from Baltistan.

Both the Shia and Sunni contingent of our group seemed to share a jovial time in basecamp. If only it was that easy everywhere. Although women in this part of rural Pakistan have a completely different role in society and are treated very differently than in the west, Beth and Juliette were shown respect, even if at times this meant they weren’t spoken to directly or made eye contact with. We all had a good bond and mutual respect between our eclectic team of nine, sharing evening stories, music, and dancing.

" THE NORTH FACE EMPTIED INTO A TOTALLY DIFFERENT REMOTE VALLEY, FROM WHICH WE WOULD THEN HAVE TO NAVIGATE A WAY OUT. I WAS BURNING WITH EXCITEMENT. "

" THE NORTH FACE EMPTIED INTO A TOTALLY DIFFERENT REMOTE VALLEY, FROM WHICH WE WOULD THEN HAVE TO NAVIGATE A WAY OUT. I WAS BURNING WITH EXCITEMENT. "

From basecamp, Falak Sar towered 1,800m above us, presiding over the whole valley. Our plan was to establish a high camp at around 5,000m, climb the north ridge and drop into the 1,000m north face via the summit. The north face emptied into a totally different remote valley, from which we would then have to navigate a way out. I was burning with excitement and trepidation to get higher up the mountain and look at our line. Falak Sar stands at 1,500m prominence to its neighbouring peaks which also host countless potential ski lines.

While awaiting better weather, we decided to give some ski lessons to our Pakistani team. None of them had been on skis before, but they enthusiastically jumped into our boots, clipped into our bindings, and started sliding around under the close supervision of Juliette and Bine, both certified instructors in the Alps. Having a French girl teaching them to ski must have been an entirely alien experience for them, but they loved it and fast found their balance.

After a couple of tentative forays higher up the mountain to stash gear and acclimatise, we finally got a fleeting two days of stable weather. Bine, Aaron, and I set off with heavily laden packs on our summit push. Pitching our tent at 5,000m, we still hadn’t laid eyes on our prize ski line. Getting Aaron’s drone airborne, we were able to scout the north side without having to climb higher ourselves. It looked incredible. In the bitterly cold pre-dawn air the following morning, we began our ascent of the north ridge breaking trail up beautiful and exposed 45-degree slopes until we hit old black ice. Pitching this out, we realized we had gone a bit light on our climbing gear, opting for weight saving instead of robustness. Still, progressing steadily, we pushed through the altitude-induced pain to the final slopes guarding the summit.

From what we had seen on Google Earth and from our drone footage we naively expected relatively benign summit slopes, and a way to scoot around the summit to a safe entrance into the face. What we found was alarmingly different. Giant cornices on multiple sides slowed our progress to a crawl as we tried to traverse the summit. Ahead lay more complex corniced ridges, irreversible terrain if we continued. We briefly contemplated leaving our snow stake behind and rapping over the first cornice, but it was too committing. The mental image we had had of the mountain didn’t match up to reality, but that’s the nature of the game when there is little information available.

We tagged the summit, which only a handful of others had previously reached and clipped into our skis. The priority now shifted from our dream of shredding the north face to getting down safely via the only other way we could - our line of ascent. The first section involved some turns on 50 degrees-plus slopes above massive exposure. The snow was grippy and reassuring but kept us on our toes. Multiple v-threads were needed to get over the icy portion of the ridge, tying our 30m ropes together and using the Beal escaper.

Finally, we were treated to some spectacular turns on the NW-facing ridge as the sun was getting lower in the sky, the entire Hindu Kush range stretching into the horizon. Gathering our gear, we skied the rest of the 1,800m descent back to basecamp, legs satisfyingly burning. Our team was soon happily reunited on the moraine, and Sattar started firing his gun into the air.

" WE BEGAN OUR ASCENT OF THE NORTH RIDGE BREAKING TRAIL UP BEAUTIFUL AND EXPOSED 45-DEGREE SLOPES UNTIL WE HIT OLD BLACK ICE. "

" WE BEGAN OUR ASCENT OF THE NORTH RIDGE BREAKING TRAIL UP BEAUTIFUL AND EXPOSED 45-DEGREE SLOPES UNTIL WE HIT OLD BLACK ICE. "

Resting at camp, I was itching to give the north face another attempt. But we didn’t get a single other good weather window and with mixed emotions I resigned myself to the fact that there wouldn’t be a second shot at it. The day we packed up and left camp, our ski team of five made a loop via a virgin 4,600m peak, enjoying some great spring snow.

When we reached Kalam again, local business leaders and politicians put on a celebration for us, and we were solemnly presented with local Pashtun hats, with dancing ensuing around a roaring fire. The community were so stoked and as we found out, summiting Falak Sar was a big deal to them. Most of all, they wanted to shed the dark history of the Taliban and welcome foreigners to the region. They pointedly repeated the message to us, “we are not terrorists here”.

The local economy badly needs the revenue foreign tourists would bring. TV and radio news teams asked Beth how she found it to be a woman in Pakistan, clearly conscious of western perceptions. Notably, she was the only women at the party with 50 others since Juliette was sick in bed with her second bout of stomach illness. One thing we all agreed on was that the trip was a true adventure, and the locals were nothing but warm and unerringly welcoming. We were made to feel special, we were looked after, and no-one tried to take advantage of us. Pashtun hospitality is legendary in this part of the world.

As I write this, Kalam and the Swat valley has been devastated by the worst floods the region has endured in living memory. Roads, houses, hotels by the Swat River, all swept away. Increasingly susceptible to such catastrophes, Pakistan is paying a heavy price for a changing climate. Inshallah, this amazing region will get back on its feet.

Tom Grant is a member of the Jöttnar Pro Team. Find out more here.

All images courtesy of @aaronrolph